WRITER’S BLOCK: WGA STRIKE 2023

By: Asa Herron

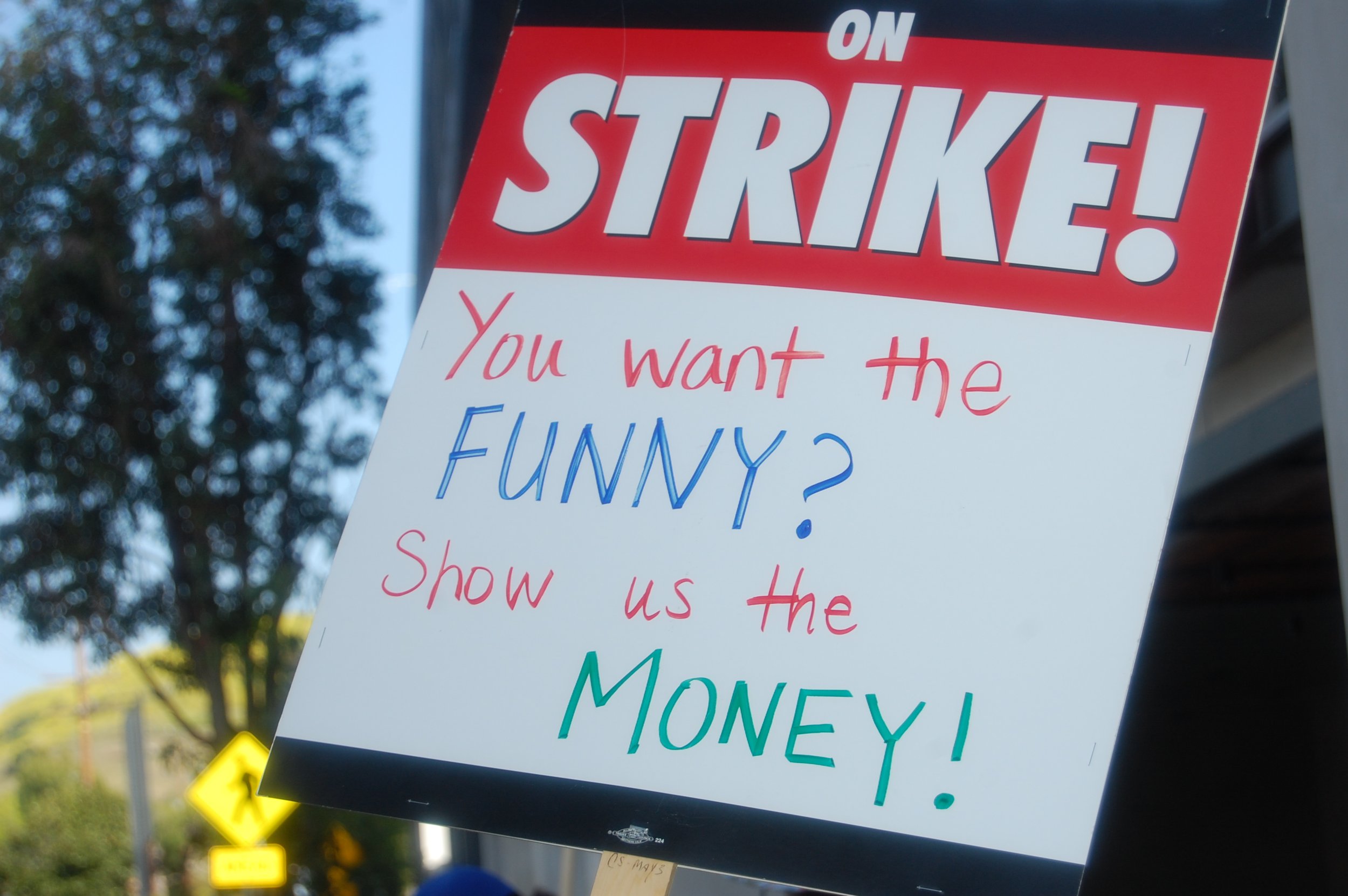

The writers responsible for your favorite movies and TV shows are on strike. Their demands are not that unlike the demands of many working Americans: fair compensation, reasonable working conditions, and protection from job loss via automation. Explore the first strike for the Writers Guild of America in 15 years as AIR hits the picket line.

FADE IN:

EXT. CULVER CITY, CALIFORNIA SONY PICTURES STUDIOS - DAY

Screenwriters belong to a union known as the Writers Guild of America (WGA). That union has voted to go on strike for the first time in 15 years, and this strike is particularly historic, professional screenwriter and WGA strike captain Eli Edelson points out, “This is our greatest voter turnout of all time, both in terms of total people who voted and those that voted to strike”. WGA Estimates put the number of “strike” votes at 98% of those that voted in the poll.

The last time they went on strike, the WGA focused their demands on updating the compensation model to accommodate new technologies like DVDs which drastically expanded the home entertainment market and studios’ profits in turn. The current strike centers around three areas in which the writers are making demands: fair compensation in the age of streaming, consistent employment, and regulation of new Artificial Intelligence-based writing technologies like ChatGPT. Their demands are not dissimilar from the demands of many working people across the country as corporations see record profits: a livable wage, supportive working conditions, and protection from automation.

What are writers asking from studios in terms of compensation? Edelson says “we’re not asking for a huge share of profits. We just want a share basically amounting to 2% of all the profits they make on the shows that we write… the studios were not willing to meet us on any of our core demands when it came to changing our compensation to adapt to everything that’s changed with streaming. All of our work has been devalued, and we just want to get it back to where it was ten years ago”. Apart from the wages paid to screenwriters while they are working on a project, they are also paid residuals. Residuals are checks paid to writers when their work is reused. This can be when a show is aired again on TV. In this way, residuals are similar to royalties in the music industry. Unlike royalties however, residuals are negotiated by the WGA and standardized across the screenwriting industry.

For years, residuals have been relied upon by writers during inevitable lapses in work between projects. Things have changed in the modern era as Edelson puts it, “there are some forms of residuals that still exist, but they are all totally degraded. For a lot of extremely successful episodes of TV - think like whatever the number 1 is on Netflix right now - the writers are not getting residuals, and that used to be our backbone for any kind of stable, middle-class lifestyle. Once we lost those, that went away and kind of became a part of the gig economy”.

As a result of screenwriting becoming a part of the gig economy, “some people have to work a second job even if they’re a credited writer in the WGA - which is so much worse than it was in the preceding years” says Edelson before adding “everyone’s hurting, and either people are out of work or they’re working but without the resources they need”.

Money is not the only resource writers need. They also need each other. Traditionally, writers work together in a writers room where they bounce ideas off of each other. This is also where younger writers gain valuable mentoring from more experienced writers. This system has been the golden goose for Hollywood which has enabled American media to be exported around the world in the last century to a degree which has never been seen before. Now, as studios pinch pennies, traditional writers rooms are shrinking. They are quickly being replaced with what are being deemed “mini rooms”.

In these mini rooms Edelson says “a lot of times you’ll get maybe half of the season written or maybe it’s most of the season written. Then all of the writers are let go, and it’s just the showrunner left to literally rewrite and produce the entire season by themself. If you can imagine being that showrunner, that’s a horrible place to be, it’s horrible for the writers who get let go, and the product isn’t going to be so good”. In an effort to fight the receding writers rooms, the WGA is demanding a minimum number of writers to be employed for projects depending on size and scope.

Trust is another resource which is not amply available to writers from studios these days. In recent years, the studios’ focus on cost cutting has been noticeable in the lack of originality of television shows and movies. Instead of embracing creativity and taking artistic risks on new ideas, proven concepts get the green light. This leaves consumers with viewing options limited to sequels and oft-repeated storylines. As Edelson puts it half-jokingly but half-depressingly, “not all TV is art, but it can be.”

Now, as Artificial Intelligence writing technologies advance, original writing is at an even greater risk. These technologies, like ChatGPT, utilize machine learning algorithms to process large swaths of data and produce whatever the user asks of the technology, namely screenplays in this case. But can this Artificial Intelligence writing be truly original work since it is riffing off of previous work? Edelson doesn’t think so since writing is “ultimately about finding creativity, and what AI can do is learn and riff off of things that have been written. In my opinion, that’s not truly original. It’s finding reworkings of what already has been. You can say, yeah, some writing is reworking stories we are familiar with, but it’s always finding that original, new human element.”

Nonetheless, originality doesn’t seem to be a priority for studios nowadays, so are writers’ jobs in jeopardy? Will the writing sector be hit with job loss due to automation in a similar way that it has hit manufacturing over the past few decades? Edelson believes that writers’ jobs are safe for now because they have something which writing necessitates and AI lacks “a heart and soul”.

What if studios decide that writers’ hearts and souls are not helping their bottom line? If it comes to that, the WGA wants to be prepared, so as part of this strike, they are demanding protection from AI job replacement. Under current contract conditions, Edelson sees writers’ intellectual property as being unprotected as he explains “for example, if they start replacing writers on Law & Order and running the procedural formula through AI, writers who wrote previous episodes are not going to get a share of whatever is produced riffing off of them in AI.” Ideally, writers like Edelson want a world in which they can utilize AI in their writing, but are not at risk of losing their jobs or intellectual property rights. He says “We want it to be a tool for writers, and writers are using it as a tool right now. But we just don’t want it to impinge on our rights to what we have written. We’re trying to get the studios to come and agree to that. It’s very indicative; (studios are) basically saying ‘we don’t even want to talk about that’. We’re like ‘Oh, why not?’. It’s because they know it’s important.”

This is an important fight, not just for screenwriters, but for workers across all sectors fighting for fair treatment in a time when corporations are seeing record profits. Although not a member of the WGA, nonfiction TV writer LEIZEL OLEGARIO saw the importance of this strike and was inspired to join the picket line because “it can’t just be one person. You need lots of people. That’s why guilds and unions are important...every time you see a certain field fight for their rights and labor, it gives encouragement to others like ‘hey we could do this for ourselves’” Striking for fair labor has even brought her in touch with her heritage. “I’m Filipino, and it’s Asian Heritage Month, so one thing I like to bring up is that I had to learn in a women’s history class [in college] that Filipinos in Delano, California did a grape strike. It propelled the farmers’ rights movement. I have a lot of pride knowing that they wanted - not just for themselves but other farmers - to be treated fairly. Now, especially after the pandemic, people are reevaluating their work-life balance. They’re no longer just grateful to have a job. There can’t be this disparity where you have a CEO who has a multi-million dollar house but doesn’t want to give us health benefits. It doesn’t make any sense for us. My name being in the credits is not enough. It’s about being treated fairly.”

The WGA strike is building momentum and inspiration for laborers to stand up for themselves and demand that their rights are fulfilled. History has proven that if laborers do not fight for fairness, they will not be compensated appropriately, given appropriate working conditions, or protected from automation. For more information on the strike and how you can help, visit www.wga.org.

THE END.